Brik à L'Oeuf: The Tunisian Treat That Tells the Story of Marseille

When I dream of Marseille, I am salty, lying on the city’s craggy beach Malmousque, the Mediterranean ocean stretching out from the limestone cliffs that fortify the city. I swig on a bière to wash down the crunch of a Tunisian brik à l'oeuf, a deep-fried pastry stuffed with potato, tuna, parsley, a runny egg, and capers, followed by an oh-so-French slice of caramel-slicked tarte tatin for dessert.

The pairing of French and Tunisian cuisines might seem more confusing than complementary. But this rebel city’s embrace of contradictions makes it so deliciously irresistible. Take, for instance, the enormous white and golden basilica Notre-Dame de la Garde, which winks in the sun as the smell of the city’s overfilling trash bins wafts by. And at Vieux Port, leathery fishermen butcher tuna fish with cigarettes hanging from their mouths as a busker plays the West African kora dreamily nearby. The city’s dichotomy inspired the philosopher Walter Benjamin’s understanding that “ugliness could appear as the true reservoir of beauty.”

I associate brik—even more so than buttery croissants—most closely with Marseille, France’s second-largest and most multicultural city. This is true thanks to the many residents who made and remade the city, paving the way for Armenian, Comorian, Vietnamese, and Maghrebi immigrants who now collectively constitute much of the so-called Marseillais population.

In this “city of 100 neighborhoods,” residents identify more as Mediterranean than French and are both physically and emotionally closer to the Maghreb region of North Africa than Paris. An estimated 40% of Marseille’s immigrants come from this region, with many emigrating here during both the post-war decolonization of the 1950s and 1960s and in the aftermath of the 2011–2012 Arab Spring.

From the moment of arrival, you sense as much. Destinations on the airport bus are announced in both French and Arabic. In Noailles—the heart of Marseille’s downtown that is fondly nicknamed “the belly of Marseille” and “Sahara on the sea” due to its largely North African populace—signs and menus are written in both languages and Arabic TV shows hum in the background of cafes as people smoke hookah. The word ”yalla”—Arabic for “let’s go!”—is said so fast by the fruit and vegetable sellers of Marché de Noailles that it becomes a poem, as men in African kofia hats sip mint tea from plastic cups. The Jewish Tunisian artist Rafram Chaddad explains that, though he cannot speak French, he gets by in Marseille speaking Arabic just fine.

So it is the city’s Algerian, Moroccan, and Tunisian sweets and pastries, including brik, that fuel the city’s beating heart.

The origins of brik

Brik’s origins are contested, but it is likely that its transparently thin and crispy pastry, or warqa—the Arabic word for paper or leaf-like—has its roots in Turkish borek, a similarly flaky pastry with a variety of fillings.

The Tunisian cookbook author Hafida Ben Rejeb Latta says that “history does not tell” when the first brik was made, but its ubiquity throughout Tunisia has left an indelible mark in time. It is influenced by the many cultures that came to or passed through the country. The runny eggs are influenced by Andalusian Jews who took refuge in Tunisia after being expelled from Spain in the 15th century. The mashed potato was brought from America, wheat from the Romans, fish from the Mediterranean, and olive oil originally from Crete is now one of Tunisia’s most prized exports.

Brik’s stronghold in Marseille, like the Tunisians who brought it there, is a wink to the turntables of history. Tunisia was a French colony from 1881 until 1956, and many of the approximately 700,000 Tunisians who now live in France hold dual citizenship. The pastry is a mimicry of the “we are here because you were there” philosophy. It also illustrates how, as philosophy professor Lisa Heldke writes in her book Exotic Appetites: Ruminations of a Food Adventurer: “Influence is the rule, not the exception in cuisine—and influence runs in all directions, not only from the powerful to the powerless.”

Brik by brik

Brik has become the customary food for Tunisian Muslims in both Marseille and Tunisia to break their fast during Ramadan (about 20–25% of the city’s 860,000 residents are Muslim). It is also an everyday street food, found at Maghrebian bakeries and street stands around both cities, with a variety of iterations.

In most Maghrebian bakeries around town, you’ll typically see the cigar-shaped variety, which is eggless, making them the perfect portable snack. They might be filled with slow-cooked meat, white fish, shrimp, and cheese. Even more creative takes are those stuffed with almonds, pistachio, and figs, echoing the sweet and fruity desserts of both France and Tunisia.

But the most common kind—and my favorite—is brik à l'oeuf. These contain a whole, perfectly runny egg and are served as a starter for Tunisian meals. Shaped like a half-crescent moon, the excess crispy warqa spans outwards delicately like a wispy fishtail. Hafida and Rafram agree that the best way to eat brik is to hold each side and take a bite straight from the middle so that the yolk must be slurped up quickly like a shot.

On the Rue d'Aubagne, the artillery vein of Noailles, you can find the original of the three now hugely popular Chez Yassine restaurants, first opened in 2014 by French-Tunisian brothers, Yassine, Farid, and Ishak, and their sister, Imen. The delicacy of Chez Yassine’s brik à l’oeuf demands you be hasty so the yolk doesn’t form a puddle in your lap. There is no escaping sticky fingers latticed in yolk and crispy crumbs.

Imen says it was important for the family to open a restaurant that serves uncompromised, typical Tunisian food. “When people eat at our restaurant, they say they imagine they are back home. Some even say it is better than what they can eat in Tunisia!”

Opposite Chez Yassine, restaurant and deli Epicerie L’IDEAL sells quintessential ideas of Frenchness—tins of anchovies, delicate jars of homemade jams, homebrewed vinegar, tubs of terrine, praline, and French wine. For Imen, it is the opposite of her traditional restaurant, but it is precisely what she likes so much about it. “Epicerie L’IDEAL are our friends. The coexistence of our shops proves that everything is possible in Marseille.”

Likewise, brik is the semblance of Marseille’s many crisscrossing and colliding worlds, and for the many Tunisians who live in the city, a taste of Tunisia in France.

Where to eat brik in Marseille

Chez Yassine’s briks are served with a slice of lemon on green and yellow plates, iconic ‘70s Tunisian ceramics.

Pâtisserie Orientale Journo

Pâtisserie Orientale Journo’s brik pastry is thicker, wrapped in multiple layers in a compact triangle, and more heavily fried. If you’re not in the mood for the crunch of a brik, opt for the pillowy dough of fricassé. It’s served with a smear of harissa from a big sacred vat, where the spice gently ferments. Wash either down with icy, homemade citronnade (lemonade).

La Maison Raya

Just off Rue d'Aubagne is Rue Longue des Capucins, whose narrow streets heave in with the heady fragrances of spices, rotisserie chicken, and the smiley ladies of La Maison Raya’s baked goods, including brik. Theirs are cigar-shaped and trade the egg for cheese.

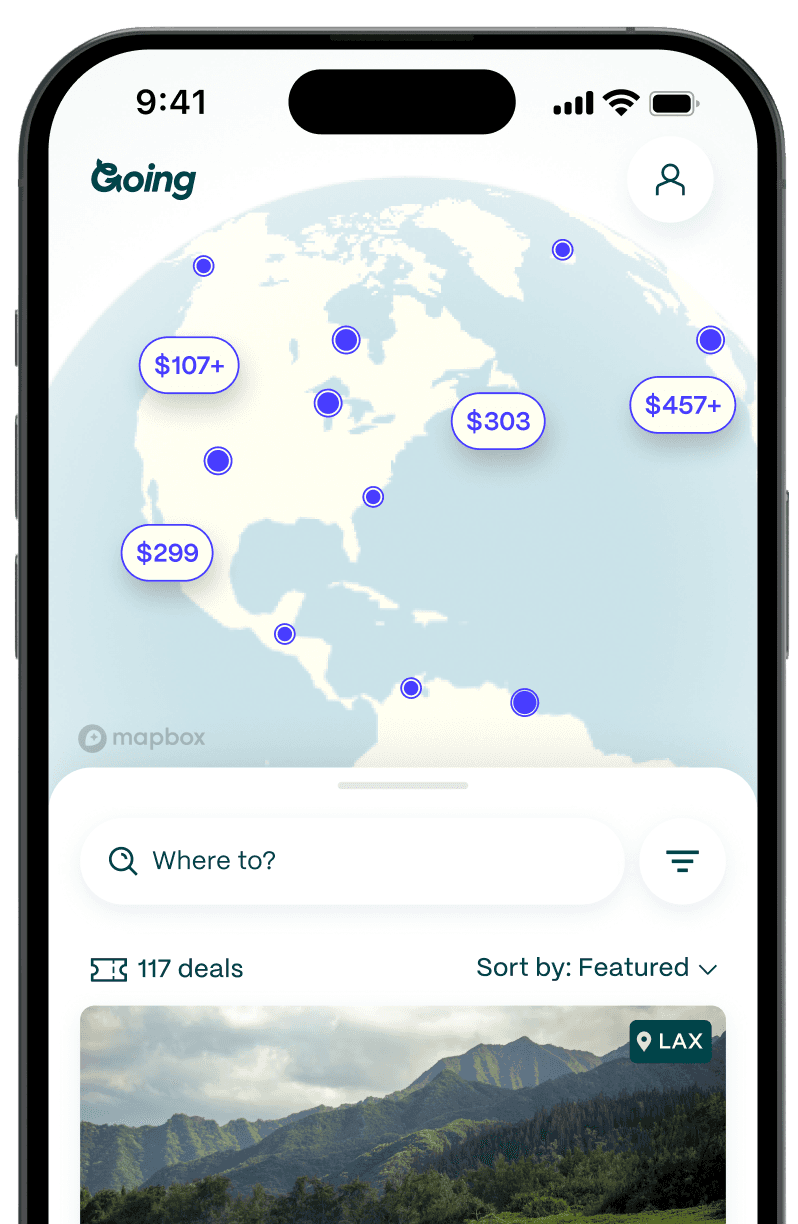

>> Join Going and get cheap flights and travel tips delivered right to your inbox.

Read more about delicious dishes around the world:

Last updated July 9, 2025